Lab 8: Forensics and Steganography Part II

From https://github.com/thezakman/CTF-Heaven

By TheZakMan | March 12st, 2021

Contents are modified with details

Esoteric Languages

https://tio.run/

An online tool that has a ton of Esoteric language interpreters.

Some of the languages are regular programming languages, but some of them are esoteric.

Brainfuck

This language is easily detectable by its huge use of plus signs, braces, and arrows. There are plenty of online interpreters, like this one: https://copy.sh/brainfuck/ Some example code:

++++++++++[>+>+++>+++++++>++++++++++<<<<-]>>>>+++++++++++++++++.--.--------------.+++++++++++++.----.-----------

--.++++++++++++.--------.<------------.<++.>>----.+.<+++++++++++.+++++++++++++.>+++++++++++++++++.-------------

--.++++.+++++++++++++++.<<.>>-------.<+++++++++++++++.>+++..++++.--------.+++.<+++.<++++++++++++++++++++++++++

.<++++++++++++++++++++++.>++++++++++++++..>+.----.>------.+++++++.--------.<+++.>++++++++++++..-------.++.

The language consists of eight commands, listed below. A brainfuck program is a sequence of these commands, possibly interspersed with other characters (which are ignored). The commands are executed sequentially, with some exceptions: an instruction pointer begins at the first command, and each command it points to is executed, after which it normally moves forward to the next command. The program terminates when the instruction pointer moves past the last command.

The brainfuck language uses a simple machine model consisting of the program and instruction pointer, as well as a one-dimensional array of at least 30,000 byte cells initialized to zero; a movable data pointer (initialized to point to the leftmost byte of the array); and two streams of bytes for input and output (most often connected to a keyboard and a monitor respectively, and using the ASCII character encoding).

Commands

The eight language commands each consist of a single character:

| Character | Meaning |

|---|---|

> |

Increment the data pointer (to point to the next cell to the right). |

< |

Decrement the data pointer (to point to the next cell to the left). |

+ |

Increment (increase by one) the byte at the data pointer. |

- |

Decrement (decrease by one) the byte at the data pointer. |

. |

Output the byte at the data pointer. |

, |

Accept one byte of input, storing its value in the byte at the data pointer. |

[ |

If the byte at the data pointer is zero, then instead of moving the instruction pointer forward to the next command, jump it forward to the command after the matching ] command. |

] |

If the byte at the data pointer is nonzero, then instead of moving the instruction pointer forward to the next command, jump it back to the command after the matching [ command. |

(Alternatively, the ] command may instead be translated as an unconditional jump to the corresponding [ command, or vice versa; programs will behave the same but will run more slowly, due to unnecessary double searching.)

[ and ] match as parentheses usually do: each [ matches exactly one ] and vice versa, the [ comes first, and there can be no unmatched [ or ] between the two.

Brainfuck programs can be translated into C using the following substitutions, assuming ptr is of type char* and has been initialized to point to an array of zeroed bytes:

| brainfuck command | C equivalent |

|---|---|

| (Program Start) | char array[30000] = {0}; char *ptr = array; |

> |

++ptr; |

< |

--ptr; |

+ |

++*ptr; |

- |

--*ptr; |

. |

putchar(*ptr); |

, |

*ptr = getchar(); |

[ |

while (*ptr) { |

] |

} |

As the name suggests, Brainfuck programs tend to be difficult to comprehend. This is partly because any mildly complex task requires a long sequence of commands and partly because the program's text gives no direct indications of the program's state. These, as well as Brainfuck's inefficiency and its limited input/output capabilities, are some of the reasons it is not used for serious programming. Nonetheless, like any Turing complete language, Brainfuck is theoretically capable of computing any computable function or simulating any other computational model, if given access to an unlimited amount of memory.[8] A variety of Brainfuck programs have been written.[9] Although Brainfuck programs, especially complicated ones, are difficult to write, it is quite trivial to write an interpreter for Brainfuck in a more typical language such as C due to its simplicity. There even exist Brainfuck interpreters written in the Brainfuck language itself.[10][11]

Brainfuck is an example of a so-called Turing tarpit: It can be used to write any program, but it is not practical to do so, because Brainfuck provides so little abstraction that the programs get very long or complicated.

Malboge

An esoteric language that looks a lot like Base85... but isn't. Often has references to "Inferno" or "Hell" or "Dante." Online interpreters like so: http://www.malbolge.doleczek.pl/ Example code:

(=<`#9]~6ZY32Vx/4Rs+0No-&Jk)"Fh}|Bcy?`=*z]Kw%oG4UUS0/@-ejc(:'8dc

Malbolge is machine language for a ternary virtual machine, the Malbolge interpreter.

The standard interpreter and the official specification do not match perfectly.[11] One difference is that the compiler stops execution with data outside the 33–126 range. Although this was initially considered a bug in the compiler, Ben Olmstead stated that it was intended and there was in fact "a bug in the specification".[2]

Registers

Malbolge has three registers, a, c, and d. When a program starts, the value of all three registers is zero.

a stands for 'accumulator', set to the value written by all write operations on memory and used for standard I/O. c, the code pointer, is special: it points to the current instruction.[12] d is the data pointer. It is automatically incremented after each instruction, but the location it points to is used for the data manipulation commands.

Pointer notation

d can hold a memory address; [d] is register indirect; the value stored at that address. [c] is similar.

Memory

The virtual machine has 59,049 (310) memory locations that can each hold a ten-trit ternary number. Each memory location has an address from 0 to 59048 and can hold a value from 0 to 59048. Incrementing past this limit wraps back to zero.

The language uses the same memory space for both data and instructions. This was influenced by how hardware such as x86 architecture worked.[2]

Before a Malbolge program starts, the first part of memory is filled with the program. All whitespace in the program is ignored and, to make programming more difficult, everything else in the program must start out as one of the instructions below.

The rest of memory is filled by using the crazy operation (see below) on the previous two addresses ([m] = crz [m - 2], [m - 1]). Memory filled this way will repeat every twelve addresses (the individual ternary digits will repeat every three or four addresses, so a group of ternary digits is guaranteed to repeat every twelve).

In 2007, Ørjan Johansen created Malbolge Unshackled, a version of Malbolge which does not have the arbitrary memory limit. The hope was to create a Turing-complete language while keeping as much in the spirit of Malbolge as possible. No other rules are changed, and all Malbolge programs that do not reach the memory limit are completely functional.[13]

Instructions

Malbolge has eight instructions. Malbolge figures out which instruction to execute by taking the value [c], adding the value of c to it, and taking the remainder when this is divided by 94. The final result tells the interpreter what to do:

| Value of ([c] + c) % 94 | Instruction represented | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | jmp [d] | Copies the value at [d] to c. Note that c will still be incremented after execution of this instruction, so the next instruction to be executed will be the one at [d] + 1 (modulo 59049). |

| 5 | out a | Prints the value of a, as an ASCII character, to the screen. |

| 23 | in a | Inputs a character, as an ASCII code, into a. Newlines or line feeds are both code 10. An end-of-file condition is code 59048. |

| 39 | rotr [d] mov a, [d] | Rotates the value at [d] by one ternary digit to the right (0002111112 becomes 2000211111). Stores the result both at [d] and in a. |

| 40 | mov d, [d] | Copies the value at [d] to d. |

| 62 | crz [d], a mov a, [d] | Does the crazy operation (see below) with the value at [d] and the value of a. Stores the result both at [d] and in a. |

| 68 | nop | Does nothing. |

| 81 | end | Ends the Malbolge program. |

| Any other value | does the same as 68: nothing. These other values are not allowed in a program while it is being loaded, but are allowed afterwards. |

After each instruction is executed, the guilty instruction gets encrypted (see below) so that it will not do the same thing next time, unless a jump just happened. Right after a jump, Malbolge will encrypt the innocent instruction just prior to the one it jumped to instead. Then, the values of both c and d are increased by one and the next instruction is executed.

Piet

A graphical programming language... looks like large 8-bit pixels in a variety of colors. Can be interpreted with the tool npiet

Execution

Codels

A codel in Piet is like an image's pixel. Some Piet programs are upscaled, meaning that a codel might not always be equivalent to 1 pixel, but a codel is always a substitute for pixels.

Color blocks

A color block is any group of codels of the same color that are adjacent to each other. Note that codels only touching each other diagonally are not considered part of the same color block; they must be touching in one if the 4 cardinal directions to be part of the same color block.

Direction pointer

The direction pointer (DP) is what moves along the program to make it run. It can be in any one of the 4 cardinal directions. The direction pointer always starts at the color block containing the upper-left-most codel, and always starts facing right. After it has executed the proper command, it will move on to the next color block that is both:

- adjacent to the current color block, and

- is the farthest in the direction of the DP.

This continues until the program terminates (see below).

Codel chooser

The codel chooser (CC) is used when multiple color blocks meet the above two criteria for the next block to be executed. Its direction is always relative to the DP's direction, and starts out facing left. When there are more than one possible color blocks to be executed, the one farthest in the direction of the codel chooser (again, relative to the DP) is the one chosen. The codel chooser can only point left or right.

Colors

Piet uses 20 colors in its programs. Each of these colors (with the exceptions of white and black) have two properties, those being hue and lightness. All colors and their properties are shown in the table below.

| Light red (#FFC0C0) | Light yellow (#FFFFC0) | Light green (#C0FFC0) | Light cyan (#C0FFFF) | Light blue (#C0C0FF) | Light magenta (#FFC0FF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red (#FF0000) | Yellow (#FFFF00) | Green (#00FF00) | Cyan (#00FFFF) | Blue (#0000FF) | Magenta (#FF00FF) |

| Dark red (#C00000) | Dark yellow (#C0C000) | Dark green (#00C000) | Dark cyan (#00C0C0) | Dark blue (#0000C0) | Dark magenta (#C000C0) |

Hue is shown going to the left and lightness is shown going down. Note that these properties are cycles, meaning that, in terms of hue, red comes after magenta. Hue always goes to the left, and lightness always goes down, meaning that going from yellow to red is 5 changes in hue, and vice versa.

White

White (#FFFFFF) is one of the two colors in Piet that doesn't fit into either cycle. White color blocks act like blank spaces. When the DP encounters a white block, it will simply go through it and move on to the next color block. No commands are executed when the DP goes through a white block.

Black

Black (#000000) is like the opposite of white in the sense that the DP cannot pass through it. If the DP tries to go to the next color block but fails because of a black block, it will switch the CC to its other state and try again. If it still can't get to the next color block, then the DP will be rotated one step clockwise. If the DP has gone through all possible states but it still can't get to the next color block, it will conclude there is no way out and the program will terminate. This is the only way to terminate a Piet program.

Commands

Piet commands aren't executed based on the color the DP is on, but instead based on the change in lightness and hue. Below is a table with all 17 commands in Piet and how they're executed.

| Hue change | Light | ness | change |

|---|---|---|---|

| No change | 1 darker | 2 darker | |

| No change | N/A | Push | Pop |

| 1 step | Add | Subtract | Multiply |

| 2 steps | Divide | Modulo | Not |

| 3 steps | Greater | Pointer | Switch |

| 4 steps | Duplicate | Roll | Input num |

| 5 steps | Input char | Output num | Output char |

- Push: Pushes the number of codels in the previous color block onto the stack.

- Pop: Pops the top value off the stack.

- Add: Pops the top two values off the stack, adds them up, and pushes the sum back onto the stack.

- Subtract: Pops the top two values off the stack, subtracts the top value from the second-top value, and pushes the difference back onto the stack. Note that if the top value is X and the next value Y, this means that Y - X will be pushed, not X - Y.

- Multiply: Pops the top two values off the stack, multiplies them together, and pushes the product back onto the stack.

- Divide: Pops the top two values off the stack, performs integer division (Python equivalent of //) on the second-top value divided by the top value, and pushes the quotient back onto the stack. This has the same X/Y property as subtraction.

- Modulo: Pops the top two values off the stack, divided the second-top value by the top value, and pushes the remainder back onto the stack. This has the same X/Y property as subtraction.

- Not: Pops the top value off the stack. If the value is 0, it pushes 1 onto the stack. Otherwise, it pushes 0.

- Greater: Pops the top two values off the stack. If the second-top value is greater than the top value, it pushes 1 onto the stack. Otherwise, it pushes 0. This has the same X/Y property as subtraction.

- Pointer: Pops the top value off the stack, then rotates the DP one step clockwise that many times (anti-clockwise if the value is negative).

- Switch: Pops the top value off the stack, then switches the state of the CC that many times (absolute value if the value is negative).

- Duplicate: Pushes a copy of the top value onto the stack.

- Roll: Pops the top two values off the stack, and then rotates the top Y values on the stack up by X, wrapping values that pass the top around to the bottom of the rolled portion, where X is the first value popped (top of the stack), and Y is the second value popped (second on the stack). (Example: If the stack is currently 1,2,3, with 3 at the top, and then you push 3 and then 1, and then roll, the new stack is 3,1,2.)

- Input: Takes an input, either as a character or a number. If the input is a number, that value is pushed onto the stack. If it's a character, its Unicode value is pushed onto the stack.

- Output: Pops the top value off the stack. If a number should be printed, the value itself will be printed. If a character should be printed, then its corresponding Unicode character will be printed.

Ook!

A joke language. Recognizable by . and ?, and !.

Ook. Ook? Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook.

Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook! Ook? Ook? Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook.

Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook? Ook! Ook! Ook? Ook! Ook? Ook.

Ook! Ook. Ook. Ook? Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook.

Ook. Ook. Ook! Ook? Ook? Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook?

Ook! Ook! Ook? Ook! Ook? Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook! Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook. Ook.

| Brainfuck | Ook! | Description |

|---|---|---|

| > | Ook. Ook? | Move the pointer to the right |

| < | Ook? Ook. | Move the pointer to the left |

| + | Ook. Ook. | Increment the memory cell under the pointer |

| - | Ook! Ook! | Decrement the memory cell under the pointer |

| . | Ook! Ook. | Output the character signified by the cell at the pointer |

| , | Ook. Ook! | Input a character and store it in the cell at the pointer |

| [ | Ook! Ook? | Jump past the matching Ook? Ook! if the cell under the pointer is 0 |

| ] | Ook? Ook! | Jump back to the matching Ook! Ook? |

| n/a | Ook? Ook? | Give the memory pointer a banana |

Steganography

StegCracker

Don't ever forget about steghide! This tool can use a password list like rockyou.txt with steghide. SOME IMAGES CAN HAVE MULTIPLE FILED ENCODED WITH MULTIPLE PASSWORDS.

At first, the secret data is compressed and encrypted. Then a sequence of postions of pixels in the cover file is created based on a pseudo-random number generator initialized with the passphrase (the secret data will be embedded in the pixels at these positions). Of these positions those that do not need to be changed (because they already contain the correct value by chance) are sorted out. Then a graph-theoretic matching algorithm finds pairs of positions such that exchanging their values has the effect of embedding the corresponding part of the secret data. If the algorithm cannot find any more such pairs all exchanges are actually performed. The pixels at the remaining positions (the positions that are not part of such a pair) are also modified to contain the embedded data (but this is done by overwriting them, not by exchanging them with other pixels). The fact that (most of) the embedding is done by exchanging pixel values implies that the first-order statistics (i.e. the number of times a color occurs in the picture) is not changed. For audio files the algorithm is the same, except that audio samples are used instead of pixels.

Stegsolve.jar

A Java .JAR tool, that will open an image and let you as the user arrow through different renditions of the image (viewing color channels, inverted colors, and more). The tool is surprisingly useful.

zsteg

Command-line tool for use against Least Significant Bit steganography... unfortunately only works against PNG and BMP images.

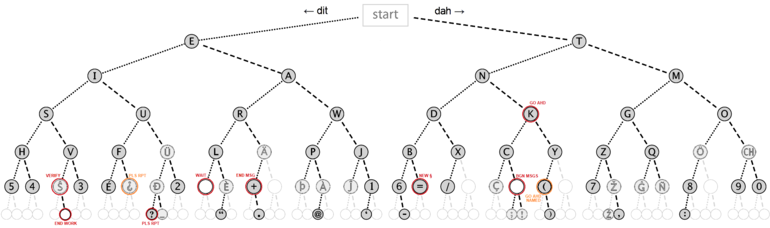

Morse Code

Always test for this if you are seeing two distinct values... it may not always be binary! Online decoders like so: https://morsecode.scphillips.com/translator.html

Whitespace

Tabs and spaces could be representing 1's and 0's and treating them as a binary message... or, they could be whitespace done with snow or an esoteric programming language interpreter: https://tio.run/#whitespace

DNA Codes

When given a sequence with only A, C, G, T , there is an online mapping for these. Try this:

SONIC Visualizer (audio spectrum)

Some classic challenges use an audio file to hide a flag or other sensitive stuff. SONIC visualizer easily shows you spectrogram. If it sounds like there is random bleeps and bloops in the sound, try this tactic!

Detect DTMF Tones

Audio frequencies common to a phone button, DTMF: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dual-tone_multi-frequency_signaling.

| 1209 Hz | 1336 Hz | 1477 Hz | 1633 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 697 Hz | 1 | 2 | 3 | A |

| 770 Hz | 4 | 5 | 6 | B |

| 852 Hz | 7 | 8 | 9 | C |

| 941 Hz | * | 0 | # | D |

Phone-Keypad

Some messages may be hidden with a string of numbers, but really be encoded with old cell phone keypads, like text messaging with numbers repeated:

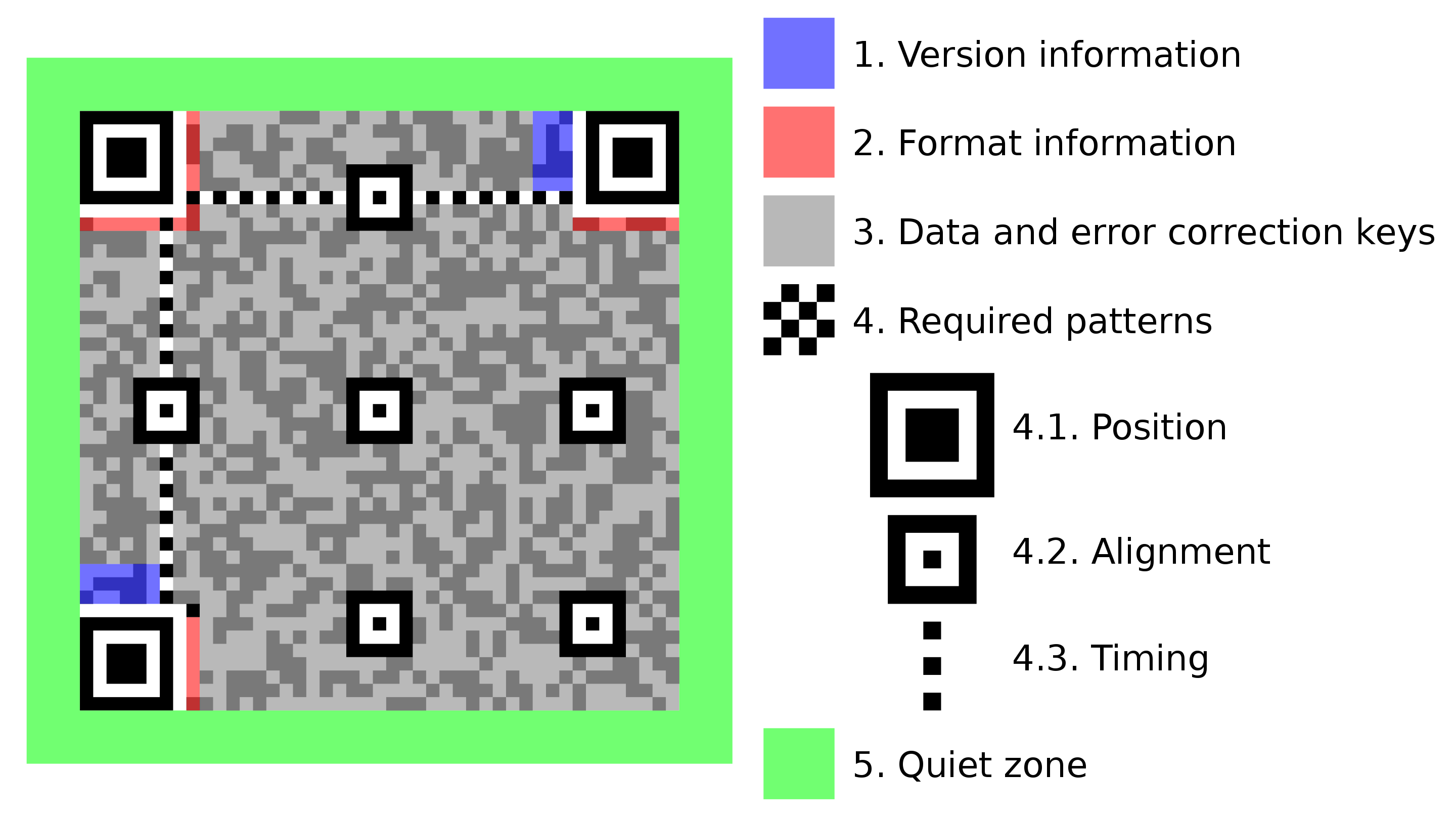

QR code

A small square "barcode" image that holds data.

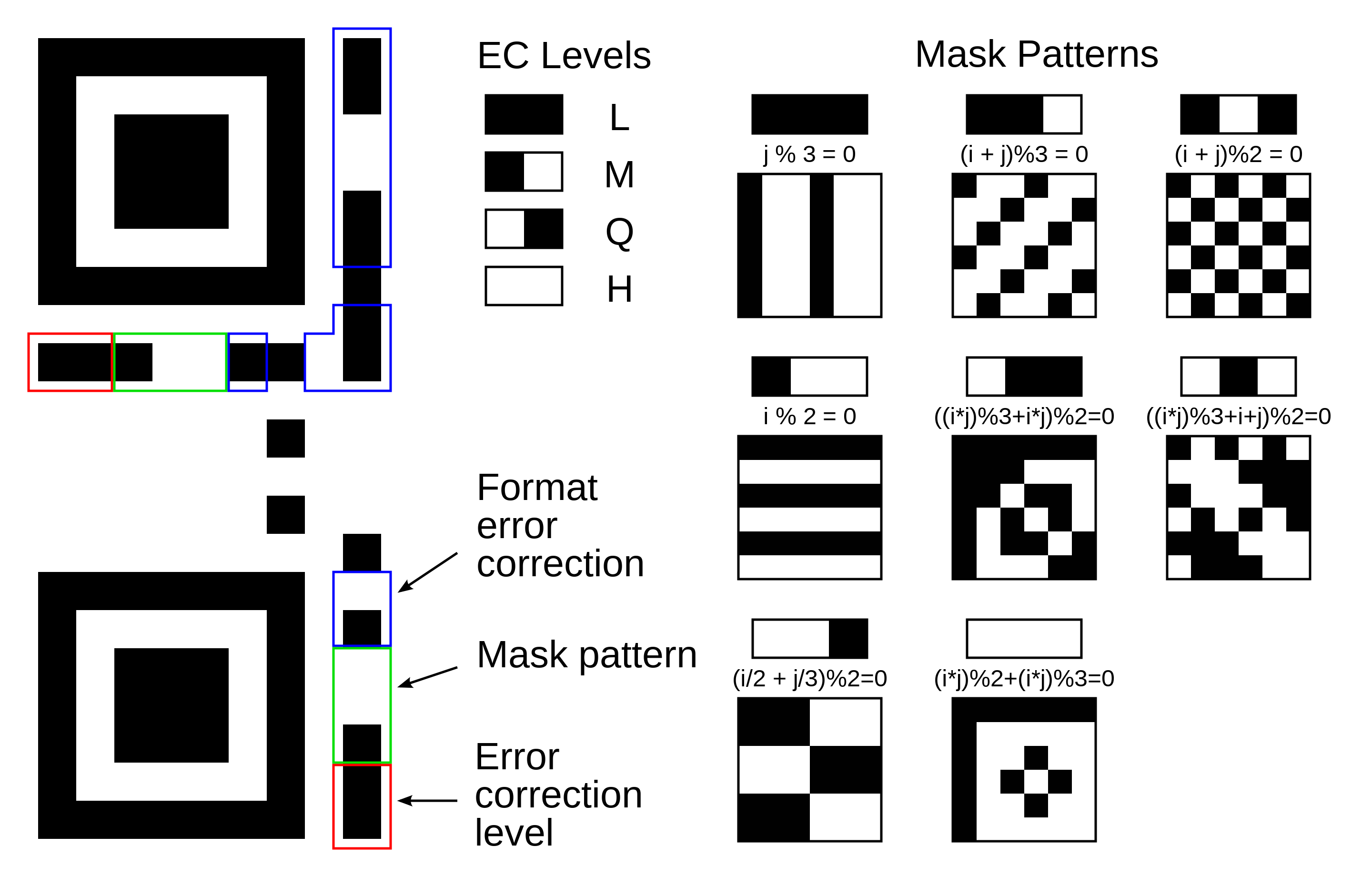

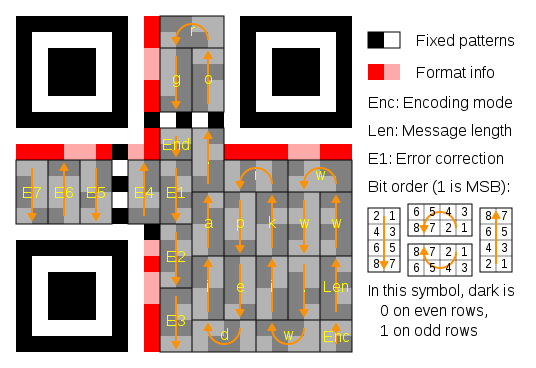

Encoding

Meaning of format information. In the above figure, the format information is protected by a (15,5) BCH code, which can correct up to 3-bit errors. The total length of the code is 15 bits, of which 5 are data bits (2 EC level + 3 mask pattern) and 10 are extra bits for error correction. The format mask for these 15 bits is: [101010000010010]. Note that we map the masked values directly to their meaning here, in contrast to image 4 "Levels & Masks" where the mask pattern numbers are the result of putting the 3rd to 5th mask bit, [101], over the 3rd to 5th format info bit of the QR code.

Message placement within a QR symbol. The message is encoded using a (255,249) Reed Solomon code (shortened to (24,18) code by using "padding") which can correct up to 3-byte errors.

The larger symbol illustrates interleaved blocks. The message has 26 data bytes and is encoded using two Reed-Solomon code blocks. Each block is a (255,233) Reed Solomon code (shortened to (35,13) code), which can correct up to 11-byte errors in a single burst, containing 13 data bytes and 22 "parity" bytes appended to the data bytes. The two 35-byte Reed-Solomon code blocks are interleaved so it can correct up to 22-byte errors in a single burst (resulting in a total of 70 code bytes). The symbol achieves level H error correction.

Assignment

(1 - Easy) ShuoDeDaoLi

Don't view the image...

(2 - Medium) QR or not QR

QR or not QR, this is a question. However, I can grant the image size is 310 px * 310 px.

(3 - Medium) Cyberpunk Audio

The music transferred from the moon. The last part sounds corrupted though.